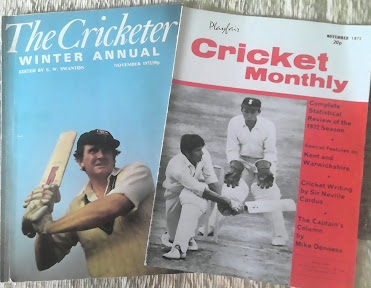

Cricketer’s November edition was always the Winter Annual in these years, a double-sized volume (though about 20 fewer pages than a standard copy these days) at the cost of 50p, or, as our grandmothers would have said at the time, ten shillings (the normal price was 20p). It is worth every p or d, with plenty of fine writing.

The centrepiece of the Winter Annual was always the

Journal of the Season. A prominent figure would write a weekly summary of

events, posting it to the offices of The

Cricketer so as to avoid augmentation with hindsight. In 1972 it was in the

hands of Tony Lewis, captain of Glamorgan but starting the transition into his

subsequent career of commentating and writing.

Lewis followed the Ashes on television, declaring that

he had become “a fan of Benaud, Laker and Dexter”, fortunately given that he

was to spend almost 20 years in the professional company of the former. He had

the distinction of recording his own appointment as captain of MCC and England on

the winter tour of South Asia. Already, he had a pleasing turn of phrase.

Dennis Lillee running in to bowl was “like a Welsh wing three-quarter in full

flight”, high praise from a man of Neath. With the moustache in common, he must

have had Gerald Davies in mind.

Some of the issues that Lewis discusses remind us of

how much has changed. He describes seeing Ken Higgs playing for Leicestershire,

and Bob Cottam for Northamptonshire as an “unreal” experience. Now, players

shifting counties happens routinely from week-to-week. Both Cottam and Bob

Willis (who had gone to Warwickshire from Surrey) had to miss the first couple

of months or so of the 1972 season as their moves were contrary to the wishes

of their former counties, a ruling that deprived the England selectors of two

possible options for the Ashes.

I had forgotten that Fred Trueman turned out for

Derbyshire in the Sunday League that year. If memory serves, he was joined by

Fred Rumsey in a partnership that was redolent of the era of round-arm bowling.

The best Journals of the Season came in the late

seventies when they were in the hands of Alan Gibson, who is given a page to

reflect on the season in this edition. Gibson aficionados will be pleased to

find that the first paragraph is devoted not to the cricket, but to his

travails in getting to and from the cricket. Train strikes are not a new thing

in Britain.

On several occasions I had

the alarming experience of having to drive a car, something I do about as

readily as riding a buffalo. At Pontypridd, I spent an hour and a half trying

to find the ground. When I did get there, there was no play, and on departing I

took a quite spectacularly wrong turn, and found myself some while later

climbing a precipitous Welsh mountain…The following day, after triumphantly

driving from Bristol to Swansea and back, I took a wrong turning within a

quarter of an hour’s walk from home, and managed to cover another twenty miles

before I arrived. The God in the machine is too strong for me.

Much of the article is a defence of three-day

Championship cricket. A four-day Championship was being mooted, though it was

not until the late 80s that it became more than talk. Gibson uses the

Championship cricket he saw in 1972 to mount a case. I am a sucker for a Wilf

Wooller anecdote and he refers to one of the best, Wooller’s offer over the PA

system at Swansea (as Secretary of Glamorgan) to refund spectators their

admission money as Somerset under Brian Close were being so boring.

The problems with three-day cricket were evident in

1972, and I think that its abandonment was correct, but we would all throw our

hats in the air in celebration of Gibson’s final paragraph:

I do not get too depressed

about the future of the championship, because however they pitch it, it has

already shown itself to be a nine-lived sort of cat.

The

Cricketer maintained an extensive network of international

correspondents, the only source of news of overseas domestic cricket in the

pre-internet age. RT Brittenden was their man in New Zealand. Later, it was

Dave Crowe, father of Martin and Jeff. When he passed away suddenly soon after

I moved to New Zealand, I emailed The

Cricketer offering my services. They replied saying that they were

wondering why they had not received his copy, and appointed Bryan Waddle.

In November 1972, Brittenden’s column was a profile of

all-rounder Bruce Taylor. Hindsight can make fools of us all.

Taylor dearly loves a

little flutter on the horses. When he takes a bet, the other runners might as

well stay in their stalls. If there is a team sweepstake, Taylor will win it.

In a mild sort of way, he has a Midas touch.

That may have been Taylor’s own view. Some years later

he served a prison sentence for fraud as he attempted to service his gambling

debts.

The Indian correspondent, KN Prabhu, has some advice

for Lewis and his tourists that remains good today: “it is good to remember that

what is funny in Coventry may not be as funny in Calcutta”.

The appointment of David Frith as Deputy Editor of The Cricketer was announced. Fifty years

on, Frith described the circumstances of that appointment in the most recent

edition of The Nightwatchman. It was

partially due to Richard Nixon. A

few months previously, Frith had written about tracking down the old

Australian pace bowler Jack Gregory, who he located in Narooma, 100 miles south

of Sydney.

Gregory was suspicious of journalists, having been stitched

up years before. He was about to go fishing when Frith cold called, but was

watching live TV coverage of Nixon’s visit to China, which gave Frith the

chance to stay and interview Gregory without the subject being quite aware of

it.

John Arlott secured Frith an interview/audience with EW

Swanton, held behind the broadcasting boxes at the Oval during the final test. It

turned out that Gregory was a boyhood hero of Swanton’s, and when the penny

dropped that Frith was the man who had found him, the matter was settled.

Frith was the most significant figure in the world of

cricket magazines for the next generation. He soon became editor of The Cricketer, and later founded the Wisden Cricket Monthly. I particularly

enjoyed his book reviews, in which he would hunt down factual errors like a dog

sniffing out truffles.

Tracking down fast bowlers was his speciality in 1972. In

this edition it is Eddie Gilbert, the indigenous fast bowler who played for

Queensland in the 1930s, but not Australia, despite being described by Bradman

as the fastest bowler he ever faced.

This time, Frith thought that he was undertaking

historical research; he visited a psychiatric hospital in Brisbane in the hope

of settling the date of Gilbert’s death. Instead, he was astonished to be told

that the bowler was still alive, and resident at the facility, to which he had

been committed because of mental illness that was the consequence of

alcoholism. This was a common fate among people who were treated deplorably by

the Australian Government.

This was not a nostalgic meeting like that with

Gregory.

He shuffled into the room,

head to one side, eyes averted, impossible to meet…Five feet eight with long

arms: the devastating catapult machine he must once have been was apparent.

‘Shake hands Eddie,’ his

attendant urged kindly.

The hand that had

propelled the ball that had smashed so many stumps was raised slowly; it was as

limp as a dislodged bail. He was muttering, huskily and incoherently, gently

rocking his head from side to side.

There is plenty more good writing in the Winter Annual. Alan Ross carries off the

tricky job of reviewing the editor’s autobiography, Sort of a Cricket Person, with

balanced aplomb. The farceur Ben Travers recalled his friendship with Vic

Richardson, Australian captain and grandfather of the Chappells. Humphrey Brooke

analysed Hammond’s tactics in the Oval test of 1938 (what distant history that

seems, but the same in time terms as a feature on the 1988 summer of the four

captains would be today). Chris Martin-Jenkins profiled David Steele, three years

before he became the bank clerk who went to war and defied Lillee and Thomson.

Sir John Masterman, academic, spymaster and novelist,

contributed a piece entitled “To walk or not to walk”. After a page of entertaining

reminiscence of appalling umpiring, Masterman’s refreshing conclusion is that it

should be left to the umpires. He calls walking “mistaken chivalry”.

Playfair,

now only five issues from extinction, is thin by comparison, in both size and

quality, though it does have Neville Cardus, who writes about cricket

reporters, past and present. Cardus, somewhat improbably, claims to have been assiduous

in recording the facts, making notes after each delivery, until…

I was observed by Samuel

Langford, senior music critic of the Manchester

Guardian, a Falstaffian man, unkempt, ripe with humour, and indifferent to

the fact that frequently his flies were not buttoned. He saw me taking notes

every ball. ‘What’s all that for?’ he

asked. ‘Tear it up. Watch the game looking for character’.

This was advice that Cardus embraced with a convert’s

enthusiasm.

Myself, I never once used

the words ‘seamer’ or ‘cutter’ in all my Press Box years, writing 8,000 words

every week, from May to late August.

No comments:

Post a Comment