I’ll be

writing separately about the Gillette Cup final. My first visit to Lord’s, and

Kent’s first trophy since the First World War, are worth special commemoration,

fifty years on.

The other

prize of the week—the only other one available in domestic cricket in 1967—went

to Yorkshire, who were assured of the title when Mike Bissex was leg before to

Don Wilson to secure first-innings lead. Raymond Illingworth took 14 for 64,

all on the second (and final) day. He was on a hat-trick three times, which may

be a record. The match was played at

Harrogate, one of seven venues used by Yorkshire for their Championship

programme.

So, as it turned out, I had seen the first day of the Championship

decider, the game at Canterbury a month or so earlier. Had Kent won that one,

the Championship pennant would have flown over Kentish fields three years

earlier than it actually did. Had Underwood, Knott and Cowdrey not all been

suddenly picked by England…(let it go, just let it go).

Arthur

Milton was playing for Gloucestershire in that game. He only scored 38 in the

game, but that was enough to make him leading run scorer in first-class

cricket, with 2,089 from 49 innings, even more of an achievement as it was made

for the bottom county. Milton’s story has been well recorded. He was the last

double cricket/football England international. These days, he could open a bank

on the back of that, but not then. When when he finished playing sport Milton

became a postman, and he enjoyed it so much that when they told him he had to

retire he took up paper rounds that covered the same route.

Keith

Fletcher and Ron Headley both went to the crease 58 times in first-class

matches, both joining 68 other batsmen in passing the thousand mark. Mike Buss

of Sussex achieved this at the lowest average: 21.46.

Tom

Cartwright bowled most overs (1,194) and took most wickets (147). In common

with eight others in the top 21 of the averages, he conceded under two runs an

over.

A comparison

of the first-class averages of 1967 and 2016 shows how much the balance of the

game has swung towards the bat (then a slender thing that could be comfortably

lifted in one hand and would last for several seasons). Ken Barrington’s 68.84

would have put him in fifth place on 2016. But Barrington was 14 ahead of

second-placed Denis Amiss, whose 54.41 would have left him one place short of

the top twenty.

The reverse

is true of the bowling, of course. Jimmy Anderson’s top-placed 17.00 would have

only got him to No 13 in ’67. There were only three bowling averages under 20

last year (one of which was by Viljoen of Kent, who I’ve never heard of); there

were ten times as many in the summer of love.

The

Scarborough Festival, summer’s death rattle for so many years, featured an

England XI playing the Rest of the World. These games were an end-of-season

feature for several years in the mid-sixties. They were of historical

significance for several reasons. When in 1970 the tour by South Africa was

cancelled at the last moment, the concept of a Rest of the World team was there

waiting, ready to fill the void. The Rest of the World also played a one-day

round robin, grandly if hyperbolically called the “World Cup”, of which more

next week.

There is

also the composition of the team. Graham McKenzie of Australia, the rest an

equal mix of West Indians and South Africans, at a time when apartheid made

such a mix illegal had the game taken place within the jurisdiction of the

apartheid government. So the opening partnership of 187 between Eddie Barlow

and Seymour Nurse was nicely symbolic and would have spoiled Dr Vorster’s

breakfast the following morning.

Barlow made

another ninety in the second innings, sharing a partnership of 118 with Rohan

Kanhai, who “played, as so often, as though he could have batted with one hand”

wrote AA Thomson. England were set 373 in five hours, a target that no England

side, official or unofficial, would have contemplated going for in 1967 in any

circumstances other than a festival match. John Edrich made an aggressive 87

but Lance Gibbs induced a collapse to 179 for six. However, the Middlesex pair

of Murray and Titmus continued to be attacking in a stand of 112 in under two

hours to save the game. Thirty thousand spectators watched over the three days

and thoroughly enjoyed themselves, though they may have wondered why this sort

of enterprise could not be seen other than by the seaside in September.

It was the first time that world outside Guyana became aware of Clive Lloyd. He looked like a short-sighted librarian who had absentmindedly wandered onto the field, but then there would be a blur as he covered an unreasonable amount of ground with two of three strides, then the stumps would be in disarray, the batsman bemused in mid-pitch, wondering what had just happened.

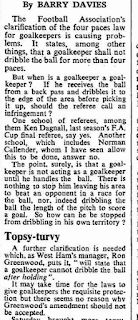

Outside

cricket, Barry Davies, then commentating for Granada and writing for The Times, reported confusion over the new

four-steps rule for goalkeepers. Did the counting start when they first touched

the ball, or when they picked it up?

Alan Gibson switched

effortlessly to rugby for the winter, starting with this report, which may have

been more entertaining than the match it described (a goal, by the way, is a

converted try, with a try worth only three points).

Mr Gilbert

Clark of Fishponds in Bristol discovered that his late wife had left their

house to a dog’s home. A trusting man, he believed that his wife had taken this

action in the belief that she would outlive him. I’m not so sure. He kept the house

but it cost him £1,000 for a dog ambulance. A grand

would have been a fair slice out of the value of a Fishponds residence in 1967.