I was pleased that Somerset won the

last Lord’s one-day final. It seemed fitting that a county outside the

metropolitan elite (in whose number Hampshire, by their own choice, are counted

these days) should enjoy county cricket’s last day on the biggest stage of all.

There was a certain personal symmetry about it too. I was at Lord’s for

Somerset’s first final in 1967, and for their first win, in 1979, the year that

we have reached in this series of posts on Lord’s finals about which I can say

“I was there”.

Britain had recently emerged from the

Winter of Discontent, and Mrs Thatcher was in Downing Street, but the state of

the nation is never representative of all its people; my own levels of content,

at the end of my first year at Bristol University, were at a record high.

I can’t quite remember why I decided

that I would go to both the Lord’s domestic finals that year, whoever was in

them. It may have been an afterthought when applying for tickets for the World

Cup final. Clearly, the price of tickets was within a student’s budget; Mrs T

had not yet taken our grants away.

Essex

played Surrey in the 55-over competition in July, while Somerset opposed Northamptonshire

in the 60-over final in September. It was a good year to be a disinterested

observer in St John’s Wood and a privilege to be present when both Essex and

Somerset won their first trophies in more than a century of existence. Tears in the eyes of grown men…“if only Dad

had lived to see this, how happy it would have made him…” etc. And there were centuries

by two great batsmen, though the greatness of only one of them was apparent by

1979.

What John Woodcock thought of all this

I don’t know; The Times was in its

year-long shutdown and missed the 1979 season completely, so there are no

extracts from its archive in this piece.

I had watched two games in the

55-over competition before the final. My season began as it did for many of the

next 19, in the bracing April breezes of the County Ground in Bristol. Gloucestershire

despatched Minor Counties (South) with ease, Procter 11-5-18-2 and 82 not

out. Two weekends later I returned to Kent

for the visit of Middlesex. John Shepherd took three wickets for one run

early on, and the Londoners reached 178 only because Mike Gatting and Phil

Edmonds put on 75 for the sixth wicket. Knocking it off would be, we thought, a

matter of routine, and I felt superior in already having my final ticket when

everybody else would be scrabbling for theirs later. Kent were all out for 73,

their lowest List A score (but, as we will see, not for long).

So to the final. I got to Lord’s, as

I did for most of these finals, soon after the gates opened at nine. My basic

ground admission ticket gave access to the lower tier of around much of the

ground. For all the finals in which Kent

were not involved I watched from the stands at the Nursery End at long on for

the right-handed batsman. No seats were allocated, so it was first-come-first

served, but that worked well as like-minded spectators grouped together. In my

area the ratio of people to Playfair annuals to pork pies was as near to 1:1:1

as makes no difference. Those there to drink and chant went to the Tavern Stand

(this group was bigger for the July finals, outside the football season). Short

people could choose not to sit behind tall people. The insistence on sending us

all to particular seats was one of the reasons I stopped going so regularly,

particularly after I found, in 1985, that my seat was directly behind the

sightscreen.

I still like to get to grounds early,

especially on big occasions. I’d go into the museum, walk around the ground, watch

the players in the nets, and be back in my seat for the toss, won that day by

Surrey’s Roger Knight, who did what most one-day captains did then and put them

in, perhaps unwisely given that Sylvester Clarke was missing through injury and

Robin Jackman playing despite struggling for fitness.

Opening the batting were Mike Denness

and Graham Gooch. It was good to see Denness back at Lord’s, the only Essex

player to have played in a previous county final, though Gooch had been there

just a month before at the World Cup final (as had I). There he made 32 batting

at No 4, but had been left in a hopeless position by Brearley and Boycott’s adoption

of appeasement as an approach to chasing 286 (on the day of writing this, New

Zealand adopted the same method in the World Cup to chase Australia’s 243, with

equally disastrous results). Gooch had also—along with Boycott and Larkins—been

a third of a fifth bowler against Richards, Lloyd, Greenidge and the rest, but a

month later did not bowl a ball against Butcher, Roope and Lynch.

Gooch’s promise was universally

acknowledged, but at that point unfulfilled. It was four years after his

disastrous double-duck debut at Edgbaston, the last test in England where an

uncovered pitch changed the course of the game. He had returned to the England

team in 1978, filling a vacancy caused by the absence of the Packer players. In

the winter’s series against a second-string Australia he had played in all six

tests but reached fifty only in the last of them. Thirteen tests so far, but no

centuries. There were those who thought that he was another English

batsman—Hampshire and Hayes two recent examples—whose promise was no more than

a mirage.

Nobody who saw Gooch bat under the

July sun that day took that view. For the first time on a big stage we saw the

foreboding backlift, the stop-motion movement, the most reassuring front foot

in cricket plonking down to send extra cover into retreat. His 120 was one of

the four finest hundreds I saw in Lord’s finals: Clive Lloyd in the first World

Cup final, Richards a few weeks before and Aravinda de Silva’s losing effort

against Lancashire in 1995 complete the list.

When the names of overseas players

who graced county cricket in the seventies and eighties are reeled off, that of

Ken McEwan is rarely included, which is an omission. He played for Essex for 12

years, in every one of which he topped a thousand first-class runs, and was as

consistent in the one-day game, good enough to bat at any tempo. Here, he outscored

Gooch in a third-wicket partnership of 124, his 72 including ten fours.

McEwan always seemed to make runs

when I was in the crowd. The day of Princess Diana’s wedding was memorable for

me solely for his century at Canterbury. Perhaps the community of cricket

bloggers could collect famous days in history that they recall more for

cricketing reasons.

Essex reached 290, the second-best

domestic final score at that time, beaten only by the 317 that Yorkshire made

in 1965, on the day that hard-hitting aliens took over the body of Geoffrey

Boycott.

The Essex supporters around me couldn’t

have been more nervous had all their mortgages been put on the win. Openers

Alan Butcher and Monte Lynch went before fifty was on the board, then Geoff

Howarth and Roger Knight put on 91 for the third wicket. But it was just a beat

too slow, and the pressure that put on the later batsmen meant that wickets fell

regularly, the winning margin of 35 runs making it look easier than it felt, to

everybody on the northern banks of the Thames Estuary, at least.

Essex followed up by winning the

Championship later in the year, the first of seven titles secured with four

games in hand. No county has represented the soul of county cricket better than

Essex in the four decades since that first happy day at Lord’s.

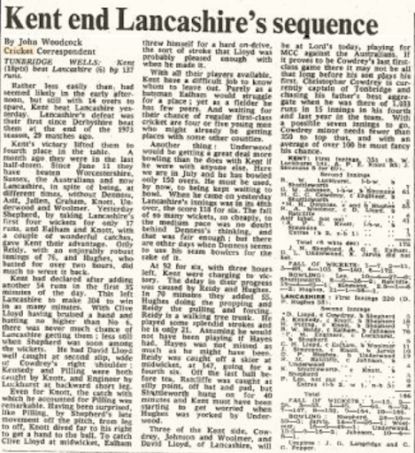

A few days before Essex’s victory, Lancashire

visited Canterbury for the second round of the 60-over knockout. Kent had

beaten Glamorgan at Swansea in the first round, Underwood 12-5-11-1.

Chris Tavaré has been attracting some attention on social media this week

having been photographed at the launch of Vic Marks’ book (which is on the list

of purchases on our September visit to the UK—we always arrive with light suitcases

and leave with heavy ones, all books). It was good that his appearance prompted

universally positive comments, admiring of the stoutest defence since Leningrad

in the forties. Even more pleasing were the one or two who remembered him as a

Sunday dasher, Clark of Kent, the mild-mannered blocker transformed into flayer

of one-day attacks. It was this persona that turned up at St Lawrence that day,

top scoring with 87 when Kent batted first, and putting on 101 with Asif Iqbal

for the third wicket. Some late hitting from Ealham, Shepherd and Cowdrey took

Kent to 278, a score that would win many more 60-over games than it lost in

that era.

Lancashire’s reply was interrupted by

the weather at 35 for one. A surprise here for younger readers: we all went back

the next day to finish the game. Cricket was not controlled by the accountants

and marketing people to the extent that it is now, so a loss-making second, or

third, day to finish the game properly was considered worth the expense.

Day two did not start well for

Lancashire, with opener Barry Wood retiring hurt a shoulder injury on 24. Wood

was good enough a batsman to play 12 tests, mainly as an opener. He had a fine

reputation as a player of pace, but suffered, as so many in that era did, from

never being given a real run. The same applied to ODIs, of which he was

selected for 13 over a decade. If had started just a few years later he might

have played ten times that number as specialist one-day selections became more

of a norm, his quality batting supplemented by scheming medium pace.

Here, he returned to the crease with

Lancashire in trouble at 124 for five and reached his hundred in under an hour,

supported by keeper John Lyon in a stand of 76 for the sixth wicket. They never

quite caught up with the required rate though and fell well short of the 22

needed from the last over.

It was Asif Iqbal who swept away the

Lancashire top order with a spell of four for five in 17 balls, probably the

most decisive spell of his Kent career. Because of a dodgy back he was never a

regular member of the attack, and some years hardly bowled at all. The

scorecard of this game suggests that he only came on because Chris Cowdrey was

getting tonked, but in heavy conditions such as those that day he could get the

red ball to swing.

It

was off to Taunton for the quarter-final. It was another of several days in

1979 when Kent folk spent the first half of the game thinking that things were

going much more swimmingly than they actually were. Dilley removed openers Rose

and Slocombe early. Richards (44) and Botham (29) were two of four victims for

Bob Woolmer’s deceptive medium pace. Somerset were 45 for four, then 128 for

eight, but Graham Burgess led a rally of the tail that produced 62 for the last

two wickets.

Burgess’s appearance and demeanour gave

the impression of his having left his blacksmith’s forge to play, though in

fact he was a ex-Millfield schoolboy. He was the only survivor of the team from

the 1967 final, and had held his place as the journeymen were replaced by

superstars. In 1979, he knew that his

time was running out and walked out to bat that day with determination borne

from the thought that his last chance of a trophy could be gone if he failed.

Even so, a target of 190 did not seem

daunting. If the last two pairs could bat with such ease, we reasoned, then the

pitch must have detoxed, making a sub-200 target an administrative matter.

What occurred was a cricketing

recreation of Wall Street in the late October of ‘29: panic, helplessness and

collapsing numbers, the Kent batsmen reduced to penury by Joel Garner. It was

the second of three occasions that summer when I watched Garner bowl an irresistible

spell that finished off the opposition, the previous occasion being the World

Cup final. Chris Tavaré went more square on when he found the

pace uncomfortably quick; here his feet pointed straight down the pitch, but he

still got one of five ducks in the Kent innings. Kent’s 60 all out remains

their lowest List A score to this day.

Watching a World Cup game from

Taunton the other day, I realised a sign of the passing years is that what is

now referred to as the “old pavilion” wasn’t built when I first went

there.

An easy victory over Middlesex in the

semi-final took Somerset into the final, where they were favourites against

Northamptonshire, just as they had been against Sussex the previous year, only

to go down by a comfortable five wickets. Just four years before,

Northamptonshire had beaten Lancashire against the odds, so the Somerset fans

were every bit as inclined to read the runes as pessimistically as their Essex

counterparts had been a few weeks before.

Viv Richards was there to reassure

them, in the same way as Gooch had, with a century. It contained many of the same

fine shots as his World Cup final hundred, but was of a different tone, as if he

had been given custody of a fine but fragile piece of priceless china that he

had to deliver safely. Watching Richards bat has been one of the greatest joys

of my cricket watching, a combination of elegance, power and pride that was

quite wonderful. Brian Rose’s 41 was the next highest score, but most of the

rest chipped in for a total of 269.

Garner started as he had at Taunton,

removing Larkins lbw in the first over, then trapped Richard Williams hit

wicket as the batsman wisely tried to put as much distance between himself and

the bowler as possible. It seemed that an early train was again an option, but

Geoff Cook and Allan Lamb put on 113 for the second wicket. Wisden says

that this took just 13 overs, but this has to be a mistake. Nine an over at any

stage was unheard of in those days, and it would etched on the memory and often

written about, surely. Lamb was three years off qualifying for England and this

was the first time that he showed his class on a big occasion. Cook was to

secure a winter in the sun on the back of a Lord’s final performance two years

later, but here was run out for 41, the beginning of the end for

Northamptonshire. Garner returned not so much to mop up the tail as expunge all

traces of its DNA, finishing with six for 29, the best bowling I saw in a

final.

Somerset’s first trophy in 104 years

was followed by a second fewer than 24 hours later. The team, the whiff of

cider in the air all the way up the M1, made their way to Nottingham for the

last day of the Sunday League, which they went into placed second. Their modest

(but in the circumstances commendable) 185 did not suggest that a double was in

prospect, particularly as leaders Kent had three fewer to chase against

Middlesex. At 40 without loss in ten overs, to us at Canterbury it looked

pretty much in the bag. We were the Habsburgs of our time, thinking ourselves magnificent

while bits of our empire were quietly seceding.

All ten wickets fell for 86 runs. News

of this inspired Somerset to induce an even more precipitous collapse, with the

last eight Nottinghamshire wickets falling for 46. A slightly surprised looking

Brian Rose accepted the trophy as if he had been doing it all his life.