There is no sentence that can tell us more definitively

how different things were in 1967 than that which follows. For several hours on

Saturday 27 May and again on Bank Holiday Monday 29 May, the only thing on

television in much of the Britain was County Championship cricket. BBC 1 had

Middlesex versus Sussex from Lord’s. Most ITV regions showed the Roses Match

from Old Trafford, while BBC Wales covered Glamorgan against Hampshire. BBC 2

did not open up until the evening, so it was county cricket or nothing.

In the event, on Saturday it was nothing, as the early

summer deluge continued. No county cricket was played anywhere on Saturday.

Most matches got going on Bank Holiday Monday, but the rain returned everywhere

but Trent Bridge on Tuesday. Kent’s fixture at Edgbaston was washed away

completely.

In the absence of any cricket to write about, John

Woodcock devoted his Monday piece in The

Times to an interview with Frank Woolley, holder for ever more of Kent’s

first-class run scoring (47,868), appearance (764) and catching (773) records.

Not forgetting 1,680 wickets, bettered only by Freeman, Blythe, Underwood and

Wright. There were plenty of people around the Kent grounds in 1967 who had

seen Woolley play, and he was always their favourite, not for the weight of the

statistics, but because of the style in which he made his runs. Woolley was

left-handed, and those who were still going strong when David Gower appeared

said that he was the nearest they had seen. Woolley lived in Canada by this

time, but returned reasonably often. I remember him sitting in the President’s

tent one Canterbury Week in the late sixties, and there is a famous photo of Woolley,

Ames and Cowdrey together in 1973, Kent’s three makers of a hundred hundreds.

Egged on by Woodcock, Woolley criticised the growing

commercialisation of cricket, this at a time when advertising hoardings around

the boundary were still a decade away on the Kent grounds. What would he have

thought of logo-laden shirts and outfields?

There was more substance in his complaint about the slow

scoring of the modern game, of which there was much evidence this week, notably

at Grace Road where on the first day against Kent, Leicestershire squeezed 155

runs from the first 90 overs. Peter West’s report notes the arrival of drinks

as the highlight of the first session (West’s piece is a rarity in that it

records a dropped catch by Alan Knott).

This exercise in reliving 1967 is unapologetically

nostalgic, but that is not the same as saying that cricket was better then. A

torpor could quite easily possess proceedings then in a way rarely seen now. When

was the last time you heard a slow hand clap? It was common enough then. A day’s

County Championship these days is likely to be more reliably entertaining than

it was fifty years ago (though uncovered pitches would be fun).

Kent lost the game because Leicestershire outdid them in

the very qualities that had served them so well so far in 1967. Their pace

attack of John Cotton (19 overs off the reel) and Terry Spencer was more

dangerous than Graham and Sayer, and Jack Birkenshaw followed a hat-trick at

Worcester by being Underwood’s equal.

Leicestershire’s other advantage was Tony Lock’s

captaincy. Lock was lured back to English cricket from Perth by the offer of

the captaincy at Grace Road. By 1967, his third season, he had brought about

something of a renaissance (or perhaps simply naissance). Ray Illingworth

completed the job, with five trophies in five years in the seventies.

Meanwhile, Lock repeated the trick in the southern hemisphere, leading Western

Australia to their first Sheffield Shield in twenty years. In 1967 he was still

good enough for Peter West to describe him as the finest slow left-armer in the

country, and was to be called up to join the MCC party in the Caribbean in the

winter.

Earlier in the week, Leicestershire visited Worcester

where 22 wickets fell on the Bank Holiday Monday. Off spinner Birkenshaw took

his hat-trick as Worcestershire were dismissed for 91. Len Coldwell and Jack

Flavell then bowled 35 overs between them (though not unchanged this time),

taking nine wickets as Leicestershire gained a lead of 20, which Worcestershire

overcame by the end of the day, though with the loss of two further wickets

only for the rain to return on the third day.

I tweeted the result of the second XI match between Kent

and Worcestershire at St Lawrence. It is not the intention to make this a

regular feature unless something noteworthy occurred, but I was there for the

first afternoon and remember two things about it. First, I collected the

autographs of some Worcestershire players, including Joe Lister and Jim

Standen. Lister was Worcestershire secretary. That one man could run the club

and still find time to captain the second XI goes some way to refuting Woolley’s

view of a game being overtaken by commercial interests. Lister went on to be secretary

of Yorkshire during Boycott Civil War. Standen was the most distinguished of

the dwindling band of footballer-cricketers, having kept goal at Wembley in

winning West Ham teams in the FA Cup in 1964 and the European Cup Winners’ Cup

in 1965. Another, Ted Hemsley—at that time Shrewsbury Town’s left back—was also

in the Worcestershire team.

The other thing I recall was that I retrieved a ball that

had been hit for four and returned it to the fielder, John Dye, something that,

as a dweller of the upper decks of stands where possible, I have never done

since, though I did once dive out of the way at Maidstone from a six that a

braver man would have tried to catch. Glenn Turner made the highest score of

the match, and I probably saw him do it, the first time I watched one of New

Zealand’s finest.

The scorecard of that game reveals that batsman and

former vice-captain Bob Wilson was in the Kent side, dropped from the first

team for the first time in more than a decade. From then on he was a mere

stopgap, and retired at the end of the season. I recall at Dover in late August

somebody asking him if he was playing in the Gillette Cup Final a few days

later, a question that even a child could spot as insensitive given that everyone

knew that the answer was no.

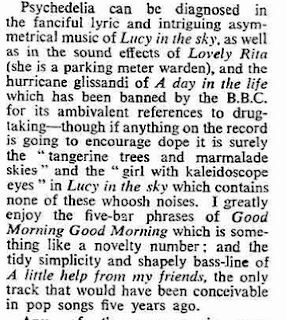

Sgt

Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band was released that week, and

received an intelligent review in The

Times.

The Summer of Love was not a universal phenomenon. The

war in Vietnam raged on, the Middle East was about to explode and now Nigeria

found itself on the brink of a civil war. The coastal province of Biafra

seceded from the rest of the country this week, a decision that resulted in the

Blue Peter Christmas appeal of 1968 being devoted to easing its children's starvation.