The Ashes of 1972 was one of the best: four positive

results out of five (there had been just nine in the previous 26 Ashes tests),

some fine cricket directed by a couple of great captains, and, best of all, a

couple of conspiracy theories that provoke anger and resentment to this day.

Mention Headingley ’72 to an Australian and watch their

brow furrow and the phrase “doctored pitch” form on their lips. England fans of

that era will reply with a question: from where did a bowler from the dry air

of Perth summon a degree of swing of which Sinatra would be proud to take 16

wickets in his debut test?

Bob Massie was the bowler and it earned him a place on the

cover of the August edition of The

Cricketer. John Woodcock, reporting from Lord’s on the second test, supplied

various explanations. The atmosphere was “heavy and humid” for the first three

days; Massie “confounding England’s batsmen by bowling round the wicket at

them” (the bounder); England replaced an unfit Geoff Arnold with JSE Price, a paceman,

instead of Tom Cartwright, or another bowler better suited to the conditions.

But for Woodcock the main reason was a failure of batting.

And at no time did England’s

batsmen bat as England batsmen are meant to.

He lists the most recent individual scores of England’s

top three, Boycott, Edrich and Luckhurst, all Ashes winners 16 months

previously, and finds only one century and three half centuries in 34 visits to

the crease.

It was possible to bat on the Lord’s pitch. Greg Chappell

did so sublimely, making 131 in what he rated his finest test innings. For

Woodcock:

It was a superbly judged

piece of batting, and technically of the very highest quality.

Richie Benaud profiled Massie in August’s Cricketer. Benaud is renowned as

cricket’s finest commentator, but this piece reminds us that his profession was

not leg spin, but journalism. It makes us regret that his writing was mostly

limited to the News of the World. It

is superb, the best thing in the magazine.

Benaud does not share Woodcock’s critical view of the

English batting.

I derived some amusement that

day from the people who besieged, perhaps attacked is a better word, me, with

advice as to how the England batsmen should have countered Massie’s bowling.

Had that advice been conveyed to them and had they acted on it, we would have

watched a wonderful spectacle: batsmen allowing the outswinger to pass and

hitting the inswinger, or allowing the inswinger to pass and smashing the

outswinger over cover point. In addition, they would have had to take block

outside the leg stump, and on the leg, middle and off stumps; kept side-on in

the stroke and opened their stance à la Barrington when the bowler operated

around the wicket.

Massie’s 16 wickets at Lord’s constituted just over half

the total of his whole test career. His star shot across the sky but, without

the heat and humidity of Lord’s to keep it flying, it fell to Earth once more.

Some parts of the 1972 Cricketer

could be inserted into the 2022 magazine with minimal alteration. Here is the

opening of Jim Swanton’s editorial, headlined, with a topicality undimmed by

the years, The Shape of County Cricket.

To say that everyone in

county cricket is exercised about finding the best programme formula for the

future may be stating the obvious; but it seems worth stressing, seeing how

many people are dissatisfied with the fixture list à la 1972, with the Benson

and Hedges Cup now brought in to make a fourth competition, and the average

follower much muddled as to who is playing whom in what, and for how many

overs. Ideally there should not be four competitions, but – but ideally county

cricket should pay for itself.

With Swanton involved, the August edition was indeed

august.

I am pleased to report that the great CJ Tavaré continued

to score runs with abandon, with an unbeaten 152 for Sevenoaks. Other

successful schoolboys who would later make cricket their career were Jeremy

Lloyds (eight for 13 for Blundell’s) and Alistair Hignell (a century for

Denstone).

Gillette

Cup quarter-final Essex v Kent

This edition of the magazine is a touch more weathered than

the others that have featured in earlier pieces. I think that is down to it

being well-travelled. It would have been in my bag when I went to Leyton for

the Gillette

Cup quarter-final. There’s a sentence that sounds as if it comes from the Old

Testament.

Essex was still an itinerant club in those days, pitching

up somewhere for a week, then moving on. The caravan, including the scoreboard

on the side of a truck, happened to be at Leyton when Essex were drawn at home against

Kent, so that’s where the match was played, in the first week of August. It

seems odd that, at the stage of the season when many counties headed for the

seaside, Essex took themselves into London. The Hundred has adopted this

counter-intuitive scheduling half a century later.

Leyton hasn’t seen any county cricket since 1977, but

Google Maps still calls it the County Cricket Ground, and it has featured on

cricket Twitter this very week, with the Cricket Writers taking on an ECB XI

there. As an unusual 13-year-old who knew a surprising amount of cricket history,

I was aware that it was the site of Holmes and Sutcliffe’s partnership of 555 for

Yorkshire in 1932, and of the run that was lost, then found again to ensure

that they had the record. It was Jim Swanton’s failure to meet his Evening Standard deadline to report the

record that lost him the trip to cover what became the Bodyline Tour, thus

removing a key peacemaker from the scene. According to Swanton, at least.

The

Cricketer and I actually went to Leyton twice, by East Kent coach;

it rained on the first day, and Wednesday’s soaking no doubt influenced what

occurred on Thursday.

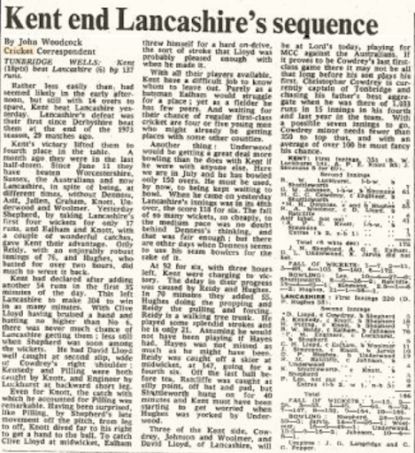

In 110 overs the two teams scored 264 runs between them, a

substantially slower scoring rate than most test matches now produce. For the

greater part of the game, defeat for Kent appeared inevitable. But just a few

weeks before, I had been at Folkestone for the

Sunday League game in which Kent’s last four wickets fell for no runs

when two were needed for victory, so I knew that hope and despair should be

kept close right to the last ball.

That Kent got as many as 137 was largely due to Asif

Iqbal, who played the most out-of-character innings of his career, 52 in 39

overs. He was well supported by Woolmer and Shepherd. The margin of victory was

the same as the tenth-wicket partnership between Underwood and Graham. The

latter made four, in which I suspect that the edge of the bat played a critical

role.

In those days, if you had 60 overs to chase a total it was

considered proper to use most of them up. People would have fallen over in a

faint had Bazball been explained to them.

In this spirit, openers Edmeades and Wallace put on 55 in

25 overs. There was method behind this caution. Derek Underwood, just back from

taking ten wickets in the fourth test, came on as first change and the

intention was to see him off. This was achieved. He conceded only 12 runs from

11 overs, but did not take a wicket.

It was John Shepherd who prised Essex open. His first five

overs were all maidens, during which he took four wickets, all to catches at

slip or behind. The last of these was that of Keith Boyce who had come from

Barbados with Shepherd seven years before. Les Ames and Trevor Bailey had spotted

the pair on a Cavaliers tour. Both became beloved by the supporters of their

counties. Boyce, the pacier bowler, had a more successful international career

with 21 tests against Shepherd’s five. Their post-cricket lives were

contrasting. Boyce died of cirrhosis at 53, while Shepherd is still hitting

golf balls 50 yards further down the fairways of north Kent than might be

expected of a man in his late seventies.

Five wickets fell for 14 runs, but 69 at two an over with

five left was not hopeless. Nowadays, there would be an attempt to hit bowlers

off their line on the basis that the fewer balls that were faced the fewer

their opportunities were to take wickets. In those more deferential times

bowlers could maintain an undisrupted line and length and let the pitch do the

rest.

The report in the 1973 Kent

Annual says that “Asif was one of several outstanding Kent fieldsmen, urged

on and inspired by Denness to rare brilliance”. This was one of the many

attractions of being a Kent fan at that time.

From the fall of Boyce on, we felt the game to be in Kent’s

hands but the later Essex order were determined, and a last-wicket stand of 19

between East and Lever had us holding our breaths once more.

Ever since those two games, at Folkestone and Leyton, I

have regarded low-scoring one-day games, with runs had to mined rather than

gathered where they fell, to be the best of the genre.

Canterbury

Cricket Week

Regular readers of Scorecards will know that I am not

sentimental about three-day cricket. As the years went on it became more-and-more

two days of going through the motions with a contrived run chase on the third.

But it could be wonderful, and the August 1972 Cricketer would have been with me at St Lawrence for a week of

three-day cricket as good as you could wish for. It was the first time since

1938 that Kent won both matches at Canterbury Week. The opponents here were Glamorgan

and Sussex.

It was Bob Woolmer’s week. He is remembered as a

ground-breaking coach and a classy batter, but for Kent in 1972 his main role

was as a medium-pace bowler, a designation that he never carried out more

effectively than here, with 19 wickets in the week. Nine of these were bowled

or lbw, five caught behind, three in the slips, so he was clearly dropping it

on a sixpence. There was some assistance from a drying pitch in the Glamorgan

game, always helpful in moving a game on, but both Alan Jones and Mike Denness

made 150s, so it was not treacherous.

Both games followed a similar pattern. The visitors batted

first, Glamorgan more effectively than Sussex. Kent replied with a score over

300, before dismissing the opposition cheaply, leaving a chase on the final

afternoon. As well as the centuries there were fifties from Colin Cowdrey,

Majid Khan, Asif Iqbal, Brian Luckhurst, Graham Johnson and Malcolm Nash.

Underwood took five wickets against the Welsh (most of them were Welsh unlike

the ersatz version in the Hundred), and Alan Knott kept wicket sublimely.

What a place, what a time, to learn to love cricket.