It was a great day, the first of the great days, the very day

when Kent’s second golden age began. Wednesday 19 July 1967, the Gillette Cup

semi-final between Kent and Sussex.

It was the first List A—one-day equivalent of

first-class—game to be played at St Lawrence (though it’s a bit tough that the

Cavaliers games had no official status). Just short of 17,000 of us crammed

into the ground that day, double the current capacity. I began on the wooden benches

at the Nackington Road End between the sightscreen and the iron stand, since

renamed after Leslie Ames. Later in the day I moved to the boundary’s edge, or

possibly beyond it; the boundary shrunk as latecomers took their places on the grass

inside the white line. Traffic across Canterbury was gridlocked for much of the

morning.

One of the first posts on My Life in Cricket Scorecards I described

St Lawrence as it was that day. As I write this, I am watching a recording

of a recent T20 game at Canterbury. So much has changed, but the winds of time

have left enough in place to make it recognisable. It has not been spoiled,

though basing the design of the new flats on the northern side of the ground on

that of an East German prison is odd (as an aside, I had thought it impossible

that there could be a worse cricket commentator than Danny Morrison, but I

listen to Andrew Flintoff at the T20 and reconsider).

Sussex, or more precisely Ted Dexter, worked out the

one-day game before anybody else and had won the first two Gillette Cups in

1963 and 1964. Before this season Kent had never beaten a first-class county,

so Sussex were favourites. Dexter had given up the game (though was to return

for Sussex and England the following year), but Sussex had John Snow, Tony

Greig—who had appeared like a whirlwind in the county game that year—, Jim

Parks and a team full of experience.

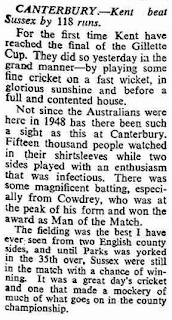

It is worth reproducing John Woodcock’s Times report in full. There is a joy

about his writing here that had been absent from his reporting on the test

series. It inspired him to reach the top of his game.

I do remember the trepidation caused by the early fall of

Denness and the slow restoration of confidence during the second-wicket

partnership between Luckhurst and Shepherd, whose contrasting styles Woodcock

describes so well. Then, Cowdrey. Yes, he could be stodgy, but on those days

when he eluded his captors of caution and reserve he was something to behold,

and that day was one of them. His 78 took just 59 balls, and late on in the

innings he and Knott made 58 in five overs. All this, bear in mind, with seven or

eight fielders back on the boundary. Kent’s 293 was worth at least 350 in a

modern 50-over game (the Gillette Cup was 60 overs).

Woodcock is possibly a little optimistic about Sussex

still being in the game until Parks was out; they were well on the way to

defeat at 27 for three. This was probably the first time that I became aware of

the tremendous feeling of being in control that Kent supporters had when Derek

Underwood came on. It was like acquiring a superpower. Woodcock’s account of

his defeat of Greig is magnificent; you didn’t trifle with Derek Underwood.

I will get around sometime to writing about my ten best

days at the cricket. The semi-final of 1967 will be one of them.

So to Lord’s, to play Somerset who defeated Lancashire

convincingly on the second day after rain took away much of the first. The

Palmer brothers, Ken and Roy, both test-match umpires in years to come,

delivered the victory, along with Fred Rumsey, Bill Alley and Graham Burgess.

Burgess was still there 12 years later on the day Kent’s golden age ended and

as Somerset’s began: all out for 60 at Taunton.

Earlier in the week, the Championship game at Southampton

(the old ground at Northland Road) vindicated John Arlott’s criticism last week

of the points system, quickly becoming a dour battle for first-innings points.

Richard Gilliatt, back from captaining Oxford University for the first half of

the season, made 122 in six-and-a-half hours, in vain as Hampshire were bowled

out four short of Kent’s total.

David Turner, to become a regular for Hampshire over the next

20 years, scored his maiden fifty in this game. Later in the week he had more

success, reaching the last eight of the National Single-Wicket Championship at

Lord’s. He beat Hanif Mohammad and Kent’s Alan Dixon before going down to

Harvey of Derbyshire. Garry Sobers won the final defeating Brian Edmeades of

Essex.

The matches were eight-overs-a-man (they did change ends)

but out was out, so some contests were very short. Fred Titmus took one ball to

overcome Clive Lloyd’s eight-ball three. There was a full complement of

fielders but no non-striking batsman. A batsman who crossed a line halfway down

the pitch had to proceed to the other end and stay there until cleared by the

umpire to return to the other end.

It was the fifth year of the competition; apart from the

first at Scarborough, all had been held at Lord’s. The following year’s

contest, at the Oval, was washed out. It returned to Lord’s in 1970, Keith

Boyce the winner and then it seems to have disappeared from the calendar.

Previous winners were Ken Palmer, Barry Knight, Mushtaq Mohammad and Fred

Titmus.

In the wider world, Britain was obsessed with sonic booms.

With the maiden test flight of Concord (the French imposed the “e” later)

imminent, some feared that living in Britain would be like inhabiting the

inside of a drum, normal conversation all but impossible because of the

mechanical thunder and the sound of windows crashing from their frames. So the

Government sent a couple of military supersonic planes to fly at maximum speed

over the capital to see what happened. It certainly created a stir over the wider

London area, with children in Billericay (and no doubt elsewhere) jumping and

crying. The responsible Minister, Anthony Wedgwood Benn treated the matter with

a good deal more levity than his later regeneration Tony Benn would have been

inclined to, cheerfully telling the House that nobody would know what Concord

would sound like until it took off.

No comments:

Post a Comment